This post was written by Anna Sofia Lippolis (@dersuchende_), who was selected to be one of this year’s DLF Forum Community Journalists.

This post was written by Anna Sofia Lippolis (@dersuchende_), who was selected to be one of this year’s DLF Forum Community Journalists.

Anna Sofia Lippolis is a Research Fellow at Italy’s National Research Council (CNR)’s Institute for Cognitive Sciences and Technologies (ISTC) and a Communications fellow for the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations (ADHO). After her BA in Philosophy, she received her MA in Digital Humanities and Digital Knowledge at the University of Bologna with a project on the quantitative analysis and visualization of authorial corrections. She has also worked as an IT consultant for projects on cultural heritage enhancement and took part in organizing two conference cycles about the present and future of Digital Humanities, “Digital WHOmanities”. Her interests include cultural analytics, quantitative approaches in literature studies and semantic technologies for knowledge organization.

I am deeply thankful for the opportunity to have helped cover this year’s conference as one of 10 Community Journalists. Being a recent graduate in Digital Humanities and a research fellow in Semantic Technologies, I was eager to attend the virtual DLF Forum 2021 to find out what best practices digital GLAM practitioners have been engaging in.

Truth of information has been a crucial theme during this pandemic and its value has been highlighted during the whole conference. As noted by Dr. Nikole Hannah-Jones and Dr. Stacey Patton when discussing the “1619” project, this means on the one hand researchers, in the broad sense of the term, need to be informed by history for their work to be held accountable in the present, while at the same time we have a responsibility towards future projects, as the infrastructures we build now will be the basis for tomorrow’s historians. Assigning values of truth to data, directly or indirectly, is also a matter of giving power to certain elements over others. It is in this sense that being informed by history reduces the risk of inequality through collaboration and inclusivity, one of the main takeaways from the DLF conference.

In the last two years, there has been increased attention to the need of online access and discoverability, thus more consideration to digitizing material reflecting under-represented communities. Online findability of resources, whose process is based on the correct handling of metadata, implies the existence of a representational framework that organizes real-world information in the best way possible and proves necessary for long-term preservation of cultural heritage. Thus, it is only by understanding why data is not neutral that we can really appreciate the value of community engagement.

Let’s take for example the project Stolen Relations, a community-centered database project, housed at Brown University, seeking to illuminate and recognize the role the enslavement of Indigenous peoples played in settler colonialism over time. As the archival documents about indigenous enslavements are written by the colonizer, the brilliant idea of an ever-present context bar in the user interface of the database has allowed users to fully understand the data. For instance, rather than simply list “tribe” affiliations, as is sometimes listed on the original document, the database aims at providing information on how archival documents often include terms that diminish the nationhood and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples (such as the word “tribe”). And in many cases, the tribal/national affiliation of enslaved Natives was completely erased.

Another enlightening talk on the matter to me has been A look into Latinx archival praxis. Mexican American Art Since 1848 is a digital portal that will aggregate Mexican American art and related documentation from dozens of digital collections in libraries, archives, and museums located throughout the United States in order to enable users to search through digitized collections of art that, as of today, are hard to find. Through culturally-informed search strategies, the team intended to pose a solution to the unidirectional understanding of arts and mainstream metadata conventions to classify artwork, which makes art created, exhibited and collected by Mexican Americans harder to digitize. Eurocentric standards and the formal imperative to select a single definitive statement for each metadata-represented concept, even when it could have multiple interpretations, actually means promoting a single narrative if appropriate context is not given. The perfect example to show that is related to the cataloguing as “vessel” of the piñata.

Mexican American Art Since 1848 ensures that all the works involved in the project are discoverable because of culturally-informed descriptors added to the metadata used by the partner institutions.

It is in this same sense that initiatives like the Wikidata Edit-A-Thon mentioned in the talk The Marmaduke Problem: Comics, Linked Data, and Community-led Authority Control, which aimed at connecting the metadata associated with a subset of the Michigan State University Comics Collection to entries on Wikidata in order to make the Collection much more digitally and publicly accessible to folks outside of MSU, are important milestones to foster discussion about addressing the gaps in digital records and the creation of linked knowledge through community engagement.

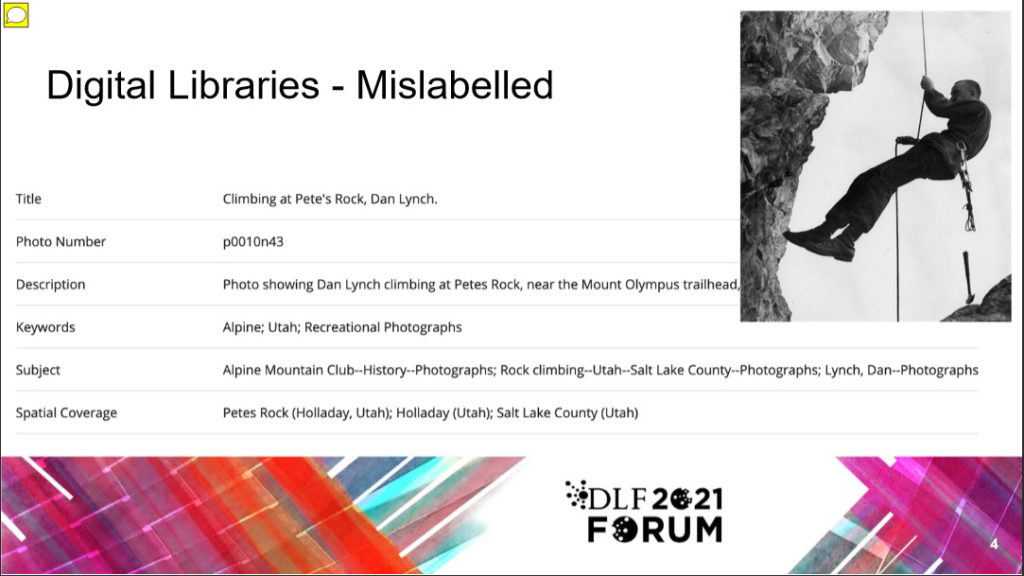

There are many other challenges concerning history-informed metadata decisions that have been presented during the Forum. They include data-rich but interdisciplinary archival materials, as shown by the The Bending Water Project at the Claremont Colleges Library, and metadata mislabelling, as the project Climbing Metadata has indicated.

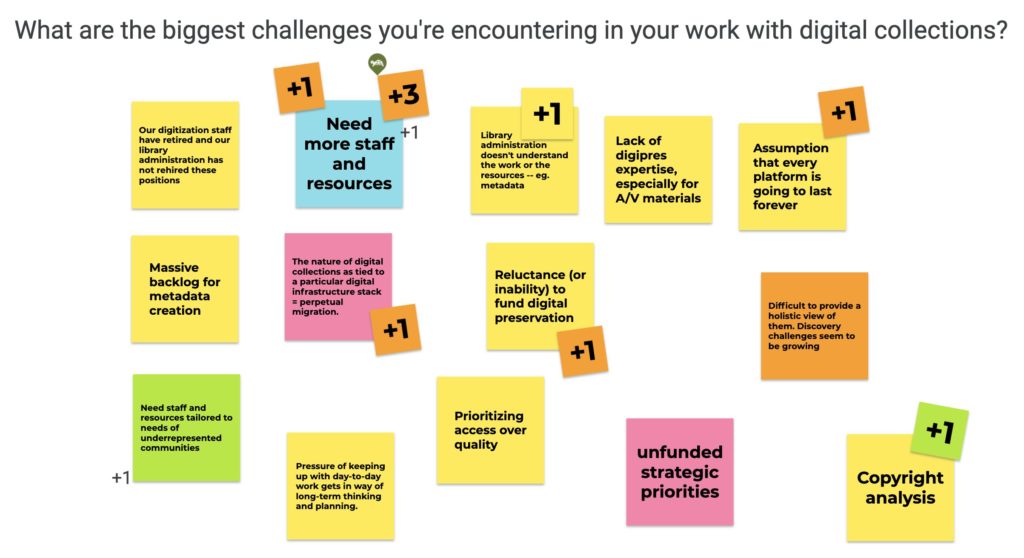

On the bright side, I think doubt can be considered a catalyst for change and the discussions with the Metadata Working Group and the Metadata Support Group have confirmed the need to build a community that is able to discuss everyday issues and long-term data preservation. The joint effort towards the development of a repository for metadata assessment tools, the collection of metadata application profiles, mappings, and practices, and blog posts that disseminate the results of this ongoing work is a model for effective knowledge sharing. The BOAF session about developing a metadata interview was, in the same way, about discussing a common framework on the matter. Questions were focused on useful interview techniques, on the support of DEI work in metadata and on the general establishment of guidelines, including project planning templates and data sheets for datasets.

Although it is obvious there are different ways to approach digital projects, the capacity to preserve them depends upon the reliability and the possibility to reuse technical infrastructures—it is a joint, long-term strategy. Along these lines Shannon O’Neill, in the panel Open to All? Creatively Imagining, Realizing, and Defending the Commons in Libraries and Archives, stated that sustainability has a much longer vision than productivity. It is why talking about the future of digital cultural heritage preservation from the point of view of GLAM practitioners, the communities involved and worldwide users has been the focus of attention during the DLF, and why doing it now is more important than ever.