This post was written by members of the DLF Assessment Interest Group’s (AIG) Metadata Working Group (MWG). Learn more about the Assessment Interest Group.

It was authored by:

Hannah Tarver (University of North Texas), hannah.tarver@unt.edu

Annamarie Klose (The Ohio State University), klose.16@osu.edu

Mandy Mastrovita (Digital Library of Georgia), mmastro@uga.edu

and edited by:

Dana Reijerkerk (Stony Brook University), dana.reijerkerk@stonybrook.edu

Rebecca Fried (Union College), friedr2@union.edu

Mandy Mastrovita (Digital Library of Georgia), mmastro@uga.edu

This collaborative think piece addresses several concerns with metadata authority control:

- Name authority records

- User interface and data display in digital collections

- Defining controlled fields and terms

- Delegating authority work to non-Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS) staff or students

We discuss systems that identify and distinguish between entities with the same or similar names, with subject authority control (identifying and distinguishing between concepts and topics) and name authority control (disambiguating people, organizations, and places). We explore how different digital libraries administer authority records to improve data accuracy and consistency as a method for improving information retrieval and user experiences.

Experts in the field providing institutional case studies include:

- Hannah Tarver (University of North Texas)

- Annamarie Klose (The Ohio State University)

- Mandy Mastrovita (Digital Library of Georgia)

Editors include:

- Dana Reijerkerk (Stony Brook University)

- Rebecca Fried (Union College)

- Mandy Mastrovita (Digital Library of Georgia)

Disentangling Personal Names and Misidentifications

Multiple Authority Records for One Person: Historical Figures

Annamarie Klose (The Ohio State University)

William Shakespeare wrote in Romeo and Juliet, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” However, names are essential in providing access to records. Entities, whether individuals, families, or organizations, can be known by various names over time and place. In the library, archives, and museum community (LAM), it is understood that using a consistent name for individuals, groups of people, and organizations is best practice. In the modern world of authority control, resources, including the Library of Congress Name Authority (LCNAF), provide records that indicate the preferred name, non-preferred names referred to as variants, and contextual information related to individuals, groups of people, and organizations described. In the era of linked data, authority records with URIs provide efficiencies in terms of sharing authority information across the Web, and it is possible to add them to MARC and non-MARC metadata. These authorities can be updated in real-time, but managing them is a voluminous task that grows much like the Web.

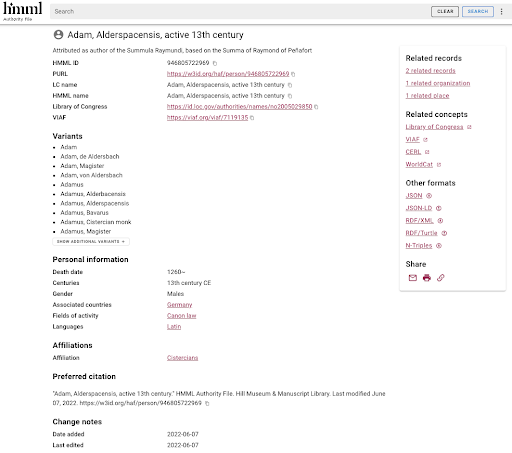

The Ohio State University Libraries has a digitized manuscript fragment from a work titled Summula pauperum from Adam of Aldersbach. Adam was a Cistercian monk who lived in the 13th century. Little is known about him, but he left several works, including this one and Summula Raymundi. While “Adam of Alderbach” was the name provided by our Rare Books and Manuscripts curator, this author is known by many names, including “Magister Adam” (“Magister” apparently means “Master” in Latin) and “Adamus Alderspacensis.” The next question is whether there is an authority record and a preferred term.

There is an LCNAF record for “Adam, Alderspacensis, active 13th century” as the preferred term and “Adam, von Aldersbach, active 13th century” as a variant. While our curator would prefer “Adam of Aldersbach,” he confirmed this is the correct individual. There is some contextual information about Adam in the LCNAF record and the information sources for this record. Regarding our local Digital Collections record, we could keep the local version of the term; however, that might confuse some users who are not familiar with that specific term. A domain-specific authority, the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library’s HIMML Authority File, also has a record for “Adam, Alderspacensis, active 13th century” that links to this LCNAF record.

However, the situation gets more complex when we look at related authorities. As per its website, Virtual Internet Authority File (VIAF) “provides libraries and library users with convenient access to the world’s major name authority files.” That can be challenging, especially with individuals like Adam, known by various names. Previously, there were four VIAF records related to this individual.

- “Adamus ca. um 1253 Magister” (https://viaf.org/viaf/307159508/) links to an International Standard Name Identifier (ISNI) record (https://isni.org/isni/0000000389329509), the NUKAT Center of Warsaw University Library, the National Library of the Netherlands, and the National Library of Poland.

- “Adamus Alderspacensis -1260” (http://viaf.org/viaf/7741818) links to the German National Library.

- “Adam, Alderspacensis, actiu segle XIII” (https://viaf.org/viaf/282716748/) links to the National Library of Catalonia.

- “Adam, Alderspacensis, active 13th century” (https://viaf.org/viaf/7119135/) links to the LCNAF term.

Since OCLC has a form to report issues in VIAF, I submitted an email about this issue and it did get resolved. Now, several of the prior authority records redirect to this main record (Now, several of Adam’s prior authority records are incorporated in this URI (http://viaf.org/viaf/307159508). This highlights the problems we face with metadata work. How we provide names and contextual information is critical for helping patrons access records. At OSU, we don’t currently have a way to add URIs to records in the Creator and Contributor fields. If that is added in the future and we have Adam’s preferred name accompanied by the URI, patrons may click the URI’s link to find his related names. Another hope is that all related authority records will link together. While some issues were resolved, the VIAF record (https://viaf.org/viaf/282716748/) from the National Library of Catalonia is still separate. Ideally, each authority would have one record for Adam – regardless of whether they have the same preferred name – and link to each other’s records. However, authority work is slow and must be handled deliberately. There may be reasons that OCLC did not merge that record with the other ones. The concept of Adam as an entity is already improved in VIAF and these changes will hopefully trickle into the related authorities.

Multiple Authority Records for One Person: Professional Publications Misidentifying Authors

Hannah Tarver (University of North Texas)

Here, a publisher used the wrong initials of an author in a professional article that has now been ingested and redistributed throughout assorted databases.

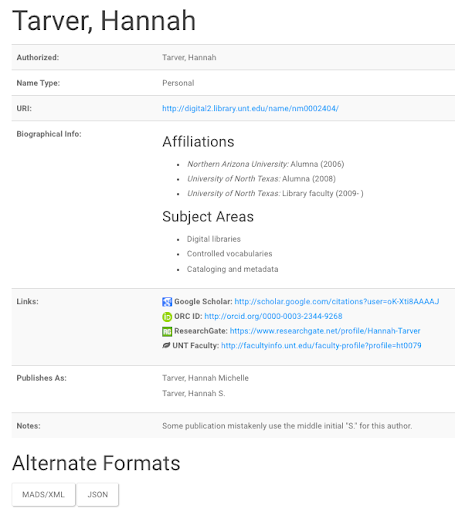

A few years ago, I happened across a journal article that listed my name as “Hannah S. Tarver” — unfortunately, my middle initial is “M.” and I do not generally use it in my academic writing. I contacted the publisher to let them know that I was one of the authors and that my name was incorrect; they fixed it and I thought that was the end of the issue. Several years later, I discovered that my name was entered with the wrong middle initial in multiple other publications.

I contacted each of the publishers and most of the publisher metadata and article versions have been corrected. However, I have also found that the alternate version of my name is included in several places that cannot be corrected, such as compiled conference proceedings that are hosted/mirrored on foreign websites. So even though I have corrected the version of my name on record in most official venues, it still exists in print, in the “wild.”

As one way to mitigate this ambiguity and provide clarification for any future researchers, I included information in the local authority record for my name to explain the situation.

Although it is a local authority, it is publicly exposed as linked data, to be findable: https://digital2.library.unt.edu/name/nm0002404/

I have also contacted the editors of various publications and asked them to change my name when it is listed incorrectly.

Still, that form of my name also exists where that isn’t an option (e.g., compiled conference proceedings mirrored/hosted on foreign websites).

But most of the time, when I come across my name, it’s in the actual record on the publisher’s site. Because these publishers don’t usually consult the Library of Congress Name Authority File (LCNAF) when they list authors (and I don’t have a LCNAF record), having an authority somewhere else wouldn’t necessarily solve this problem.

Additional Resources: Persons vs. Organizations and Parent-Child Relationships

Joshua Steverman, an application developer at the University of Michigan, has worked on a complete list of federal authors (departments, agencies, offices, employees) that would help better aid the description and organization of federal depository records, particularly in the cases of parent-child relationships within federal agencies.

In addition, he has determined implicit relationships from unauthorized use of unauthorized headings in the MARC 410 field to help automate the identification and relationship of subsidiary agencies.

Steverman and his team ultimately built a list of 50,000 United States government authors by looking through the content in the 410 field for these key identifying pieces. We recommend his article, “Problems with Authority,” on the University of Michigan Library blog.

Display of LC Name Authority Records in Digital Collections Can Confuse Patrons.

Mandy Mastrovita (Digital Library of Georgia):

Our systems and interfaces affect authority control, and what they display significantly impacts the overall process.

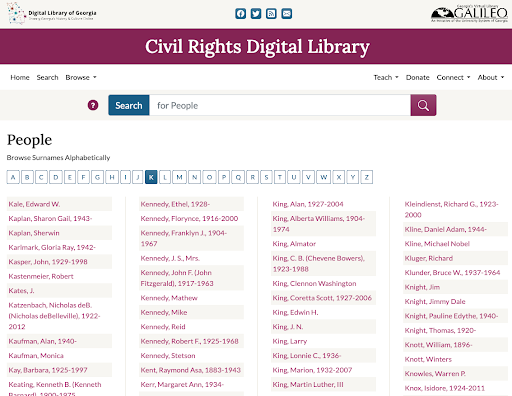

One of our most high-profile portals, the Civil Rights Digital Library, includes a great deal of name authority work to help identify civil rights workers active in their communities from the 1950s to the 1970s. Part of the work of this IMLS-funded project was to recognize civil rights “foot soldiers” and assign LC name authority headings.

Here, we find ourselves interacting directly with patrons using our site who know these individuals, and we will take vital information from them and incorporate it into the local name authority record, and ultimately into the LCNAF.

Often, after a civil rights foot soldier has died, we receive distressed help desk tickets from members of the families of these civil rights workers who have seen a name authority heading of their friend, colleague, or loved one that doesn’t include their proper death date.

We explain that in most cases, name headings were provided by the Library of Congress, not created by us. But this information doesn’t address the needs of our patrons.

In cases like these, and if there is precise information relayed to us by close friends or family members (e.g., an exact death date), we will go into our local database and revise the heading.

Ideally, we also try to return to OCLC Connexion, remediate the NACO heading, and update the record with the new death date identification provided by the family.

As one might gather, the full remediation of records like these can be a lengthy process that requires diplomacy, research, and fact-checking that an experienced librarian with name authority/NACO training would have to complete.

Configuring System Indexing for Places and Place Names

Hannah Tarver (University of North Texas):

Digital systems often have options to browse for materials about a particular location or filter search results based on geographic locations of the content. For example, in The Portal to Texas History, users can limit search results using filter menus, or choose a location from a map or list of places: https://texashistory.unt.edu/explore/locations/

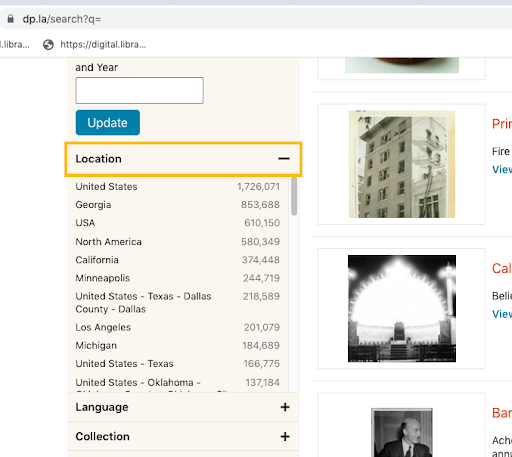

Like other forms of authority control, this functionality generally relies on consistent representation of location names, although there are many different standards for doing so. DPLA has a similar search filter based on locations, but it has many variations since the source metadata is entered according to different formatting requirement.

At UNT, we represent places hierarchically from the largest to the most minor relevant component so that we have flexibility to group materials at different geographic levels (e.g., all materials in the United States, or in Dallas County, or in the state of Illinois, etc.). Place names in our system include an entire series of geographic/administrative units, such as: “United States – Texas – Harris County” or “Greece – Attica Region – Nomarchía Athínas Regional Unit – Athens Municipality – Athens.” It also makes it easier to denote the level of specificity that we know, whether it’s just “somewhere in Idaho” or “outside Oklahoma City” (which we would document as a county) or a city.

To support browsing, we have also chosen (when possible) to represent the current administrative name for a place rather than a historic one, even when the content may reflect a location that has changed or no longer exists, such as Yugoslavia, or the U.S.S.R., or U.S. territories that have become states. (For reference, our full place name formatting guidelines are available at: https://library.unt.edu/metadata/fields/coverage.html)

Although it seems straightforward to handle locations this way, we have run into a number of problems when trying to represent names accurately. Here are some examples::

- We switched our “authority” source from the Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names (https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/tgn/) to the open-source GeoNames database (https://geonames.org) several years ago. We discovered that these entities use different Anglicizations of various names (and sometimes variations in hierarchical representations). For example, a region in Italy labeled “Lazio” by Getty vs. “Latium” in Geonames.

- Although we use current names for locations, this requires keeping up with changes, which occur periodically. In 2016, France reorganized all of their top-level administrative regions (reducing from 22 to 13). Even our “modern” place names had to be reviewed and changed for almost all materials about locations in France. (Luckily it was only around 2,500 records.)

- Historic place names can be reflected in other ways in our records, but sometimes there is not a current equivalent for the coverage place (e.g., ghost towns), which can be problematic. In some cases it makes sense to include the historic location, even though that means that not all places are represented equally; sometimes we reference the next-closest level (e.g., current county).

- There are also cultural complications with certain locations, e.g.:

- Places in Palestine/Israel (or other disputed territories)

- Sovereign locations that are not geographically distinct, such as Native communities and lands

- When cities cross county boundaries, most of the time, only one county is the “real” county according to an authority source (generally based on the city center, but this can be difficult if cities or county boundaries have shifted over time, and occasionally, it’s more complicated.

- For example, New York City spans five different counties. In our guidelines, we chose not to list a county for “New York City” and, as another exception, if a borough is known, it can be included with the county (e.g., “United States – New York – Kings County – New York City – Brooklyn Borough”) even though we usually do not include anything beyond city specification in the place name string as a rule.

- Representing a hierarchy for locations in other countries can be challenging since not all places have uniform divisions. For example, administrative divisions for locations in England vary wildly depending on the region.

Defining Controlled Fields And Terms

Mandy Mastrovita (Digital Library of Georgia) and Hannah Tarver (University of North Texas)

Differing institutional support of controlled and uncontrolled terms

Digital Library of Georgia:

- We try to capture all of the information about anything that would be needed for an archival MARC record, if one does not already exist.

- Our controlled terms are guided by international and national standards such as:

- Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) (subject)

- Library of Congress Name Authority File (LCNAF) (personal and corporate names)

- We are now adding inclusive metadata and conscious linked data guided by controlled vocabularies like Anti-Racist Description Resources, (Archives for Black Lives Philadelphia), Homosaurus, and others.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (dates)

- Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI) (document types)

- Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT) (medium)

- RightsStatements.org (standardized rights statements)

- Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) (media type)

- ISO 639-2 (language of resource)

- GeoNames (spatial data)

- We reserve the description field (e.g., dcterms_description) as a container for uncontrolled terms.

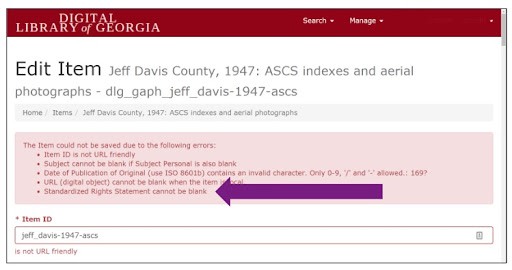

- This data is validated upon ingestion into our management system.

University of North Texas:

- In our system, we manage a number of local controlled vocabularies at https://digital2.library.unt.edu/vocabularies

- These include qualifier values and controlled values for fields that must be picked from a list (e.g., resource type, collection, institution, language, etc.)

- Maintaining the list locally allows us to tie them directly to our editing system, so that controlled values are represented as a drop-down menu

- Some vocabularies use other sources as a foundation (such as creator/contributor roles, which largely match MARC relator codes), but may also include additional, local values (e.g., “artisan”)

- Name fields (creator, contributor, publisher) are semi-controlled in our system. We maintain a local name authority file (https://digital2.library.unt.edu/name/) which is searchable in our metadata web form. Since we are largely describing cultural heritage collections, most names do not have authority files, so editors are expected to format names according to our standards when an authorized form is unavailable. We also have a number of tools for evaluating metadata values, so it is often more efficient to look at all the variant name values in a collection at the end of a project and do any clean-up or authority control at that point, rather than trying to control names over the course of a project.

- During the last year, we have also implemented authority files for place names, although they are not currently connected to editing functionality since we are manually verifying locations and geocoordinates. However, the location records are public-facing (e.g., for the Portal: https://texashistory.unt.edu/explore/locations/curated/ and the UNT Digital Library: https://digital.library.unt.edu/explore/locations/curated/) Eventually, we plan to connect the authority records to coverage place names in our system so that the field becomes strictly controlled.

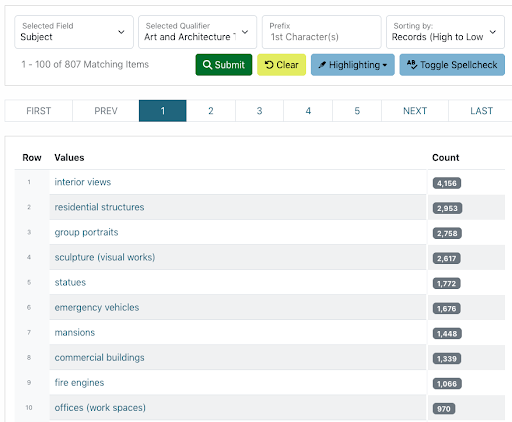

- For subjects, we support a number of different controlled vocabularies — as well as keywords and locally-defined subjects (such as named animals and scientific names) — with a field qualifier to label the type of subject value, which allows us to add any other vocabularies that a partner might want to use for a collection.

- The UNT Libraries’ Browse Subjects are locally-managed (https://digital2.library.unt.edu/subjects/) and display in a searchable pop-up modal for editors so that only controlled terms are chosen. This vocabulary is used in The Portal to Texas History to support “browse by subject”: https://texashistory.unt.edu/explore/subjects/

- Many of the vocabularies are supported, but not internally controlled or validated, e.g., Library of Congress Subject Headings, Art and Architecture Thesaurus terms, Chenhall’s Nomenclature terms, etc. For those vocabularies, if terms are available, editors are expected to copy them from the vocabulary or enter them according to the rules of the authority, with an accurate label to denote what type of subjects they are.

- Recently we implemented pop-up search boxes for certain controlled LC vocabularies that are available as linked data: Library of Congress Genre/Form Terms for Library and Archival Materials (LCGFT), Library of Congress Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music (LCMPT), and the Thesaurus for Graphic Materials (TGM). This has led to a shift toward using more controlled terms in place of uncontrolled keywords since they are readily available and do not require editors with extensive experience or knowledge of vocabularies. We also encourage the use of separate terms rather than LCSH subdivisions (e.g., for genre/form terms), which creates more cross-collection subject overlap.

- Our integrated edit tools also provide an opportunity for editors to see the most frequently-used terms from a vocabulary, which can provide useful, broad terms that will align with other metadata records, even without having in-depth vocabulary knowledge. For example, we often use general Art and Architecture Thesaurus terms for photos of buildings (e.g., “commercial buildings” vs. “residential structures”), but it is not a primary vocabulary for most terms or collections, so referencing a handful of terms to assign “categories” can be more useful than expecting someone to search the thesaurus.

Evaluating the usefulness of controlled subject terms (or subjects in general) can also be challenging. As part of a metadata research project, I recently compared actual user searches to subject values in one of our collections, to highlight major differences or gaps between expectations and practice of using free text terms versus subjects in finding items. That analysis is documented in a white paper, with other findings from the study (https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1871085/m1/29/). Metadata practitioners could evaluate the usefulness of some terms in this fashion, assuming, of course, that:

- They have access to the data.

- They have the time/expertise to analyze the data.

- They can make systemic changes based on the results, etc.

Delegating Authority Work to Non-MLIS Staff or Students

Hannah Tarver (University of North Texas), and Mandy Mastrovita (Digital Library of Georgia):

- Realistically assess the time, energy, and resources required to maintain authority control.

- Determine what can be delegated down in the workflow.

- Who can do the work? Staff? Grad students? Undergraduates?

- Note that not everyone necessarily has to do everything (e.g., for some UNT projects, students enter information available on title pages — title, creator, date, etc. — but LCSH terms are assigned by catalogers)

- Explain the role of controlled vocabularies like LCSH, Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT).

- Students often find that AAT (genre/medium) is more accessible to grasp than LCSH (subject) at first. Start with the low-hanging fruit and then work towards what is more complicated.

- Focus on how subjects connect users (by applying search terms and assessing the values they deliver)

- Cover different kinds of subjects and subject-related information.

- Look at a good OPAC (Yale’s ORBIS catalog, for example) where students can see the difference between skimpier (usually vendor-generated or bulk-ingested) records and more robust (original cataloger-created) ones.

- Don’t recreate the wheel–if that OPAC has a great heading, use it!

- Consider using a lower-barrier option like FAST, and seeing if you can train staff or students to use it when less extensive or subdivided headings are OK for your resources.

- User experience testing has proven that simpler terms are preferred to complex stringed LC headings.

- Clear instructions and supporting documentation can be very helpful references for editors, regardless of skill level.

Concluding Thoughts

The issues in authority control discussed here shed light on the complexity and significance of managing accurate and consistent metadata, particularly when aggregated, shared, or displayed in multiple environments.

- From remediating multiple authority records for historical figures to addressing misidentified authors or correctly identifying lesser-known figures in professional publications and on our websites, the challenges are complex and require thoughtful solutions.

- Representing names, organizations, and places through standardized authority records is pivotal in facilitating efficient information retrieval and enhancing user experiences.

- Collaborating with other librarians, patrons, staff, or students and leveraging all of our production options in creating records while consulting multiple authority resources like LCNAF, VIAF, HIMML, ORCID, FAST, and GeoNames, among other resources, proves crucial in navigating these challenges at all levels of creating robust and shareable/ harvestable metadata records that display correctly in dynamic Web environments while also supporting the basic search skills and natural language that our patrons use. We are building workflows that support these efforts.

- While delegating authority work to non-MLIS staff or students can be a viable option, it demands careful consideration of training and sustainability to ensure the maintenance of high-quality metadata over the long haul.

By enhancing authority control efforts and utilizing linked data options that collocate the refinements we may need to apply to our records, we can strive for better and more seamless user experiences in our digital collections. Embracing “best practices” and continuous improvement requires interaction with different services, and sometimes, multi-pronged approaches to better discover, explore, and connect our users to our resources.