This post was written by datejie cheko green (@seeksolidarity), who was selected to be one of this year’s DLF Forum Community Journalists.

This post was written by datejie cheko green (@seeksolidarity), who was selected to be one of this year’s DLF Forum Community Journalists.

datejie is a journalist, digital consultant, and interdisciplinary scholar who’s knowledge production spans genres and sectors. Her research interests include decolonial and environmental movements with a focus on uncovering and translating the histories of systems and relations that have led to inequalities today. She has been a union organizer for freelancers, equity-seeking journalists and knowledge workers in Canada and the US, leading her further into projects innovating digital justice.

Since entering journalism through community radio, datejie has tracked gaps and opportunities for more cohesive creation, publication and preservation of the work and works of marginalized peoples as journalists, and as news subjects. Her early interests in archiving radio and film led her to self study and training of research methods, cataloguing systems, digital asset management software, metadata practices, national and international preservation standards and practices.

Looking back at history and forward to posterity, datejie’s current work seeks to address the contemporary urgency for digital literacy, media literacy, news literacy through radical, collective and community—minded publishing, preservation and archiving. She is presently developing news programming and teaching modules focused on Black journalists in the African diaspora.

Digital Librarians: the public-access superheroes powering (and saving) the information age

When I was a child in the pre-digital era, I used to marvel at libraries: The vastness of the shelves, the intricacy of the card catalogues, the detail of the Dewey Decimal System, the craft paper posters and signs. And that library smell… of books and wood and carpet, a clean smell that somehow made fragrant the very stillness of focussed minds in discovery.

All of it was thanks to the collective intentions and labour of librarians.*

When the technological revolution of computing threatened to render that iconic engagement an artifact of itself, I watched in awe of librarians’ willingness to step into an abyss that many predicted they would never survive: the digital age. Against the shock of “adapt overnight” or face obsolescence, whole cohorts straddled the trenches of mass data entry on one side, while inventing some of the first electronic list-serves on the other. These digital communities of practice originated the collaborative, remotely distributed teams we use now, and their public-serving praxis forged the Digital Library Federation’s (DLF) founding purpose in 1995: To create a distributed, open, digital library.

As the keepers, trackers and sorters of collective public knowledge, librarians have been the front line workers of a runaway information age driven by everyone else but them. They’ve had to respond to the combined innovation of military and computer scientists who developed the internet, corporate manufacturers of computers and smart devices driving consumption, telco internet service providers who set the pace for commercial user agreements and cooperation with governmental surveillance, and software companies offering “free” services while secretly collecting our personal information and internet habits as data for undisclosed purposes.

The centrifugal growth of these drivers has outpaced public education budgets, all the while forcing mass scale public engagement with the digital knowledge economy. Throughout, DLF professionals have contributed countless hours of technical, operational and ethical service and innovation, their bodies and livelihoods frequently standing in the gap to advocate for people before profit, often with dire consequences on worker health and sectoral retention.

Digital librarians are standard-bearers of the public interest in the present, and for generations into the future. They have inherited a deeply invisible moral pressure that big tech roundly eschews, one that, by design, places them at the contradictory intersection of professional undervaluation and civic indispensability. For institutions and repositories of learning, arts, culture and human knowledge that have stared down this digital reckoning and survived, it’s been those at the forefront of justice that have distinguished themselves and become best prepared for the Covid-19 pandemic, its meta-phenomena of socio-economic and digital inequalities, and the opportunities within.

As a non-librarian, a critical journalist and Black digital humanist, my awareness of this backdrop made my participation in the DLF Forum 2021 a thoroughly transformative experience.

Through its alliances, I saw glimmers of how DLF professionals and community partners are quietly emerging as a superhero network of intercessors for the global public good in the information age. Their leadership in the turn toward integrated, intersectional digital justice in the systems and structures of academia and other public sectors is becoming more vital by the minute. I kept thinking that, with serendipity, increasing value alignment worldwide, and the digital convergence afoot between formerly disparate sectors of big tech and data, libraries, the humanities, social justice movements and mass communications, the DLF’s1995 vision for a distributed, open, digital library has the potential to go global and go big. And in this, librarians and their labours must be justly recognized and rewarded.

For more than two decades, global grassroots digital justice agitation and theorizing in Black, Indigenous, feminist, disability, decolonial, environmental and labour rights sectors has generated the social discourse and cultural awareness that is defining our current moment. The DLF Forum 2021 showcased the uptake and integration of these schools of life into their future-focussed schools of thought and practice.

Projects that would have been inconceivable a decade ago demonstrated the type of dreaming, planning and action toward digital justice that can also create conditions toward rehabilitation and reconciliation. The adoption of global Indigenous meta/data ethics (https://www.gida-global.org) into the University of Oklahoma historical and digital collections and the innovation of distributed digitization and preservation through the HBCU Library Alliance (http://www.hbculibraries.org/), bringing African American educational history online into the hands of descendants, wherever they are, were just two examples.

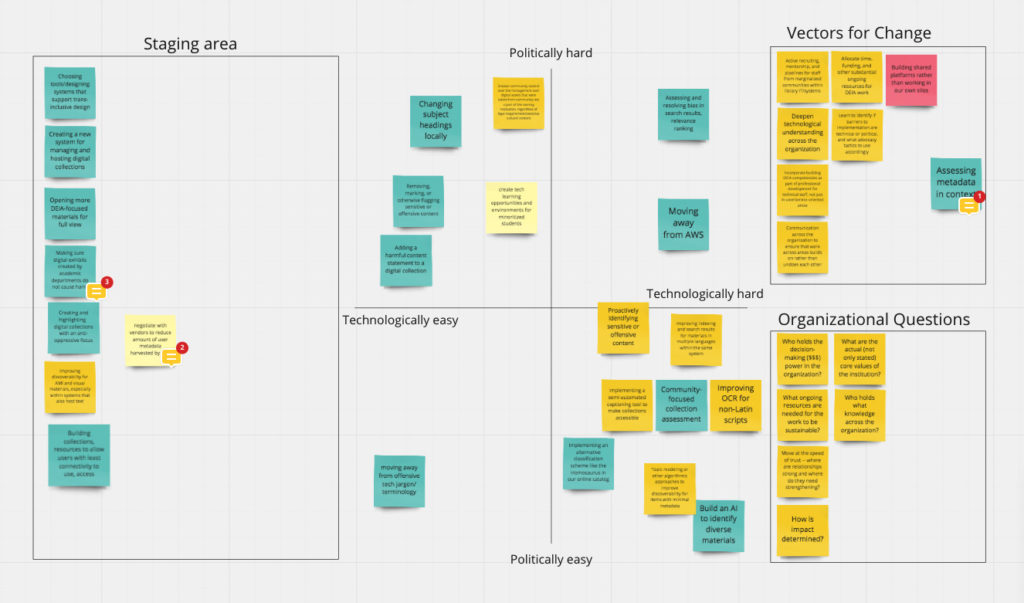

This Miro Board from the session, “Towards a Structural Approach: How Do We Address the Root Causes of Bias and Inequality in Digital Environments?” also offers a glimpse into the range and rigor of the Forum.

.. Each of these virtual whiteboard stickies represents people groups striving for equitable, meaningful and just participation in the digital age. Such goals require bringing excluded people into the spaces where the technologies, collections and systems are created and housed… not just as consumers, but as thinkers, producers and generators of information, technologies and how this information is used and accessed. And this requires the transformation of the cultures of those spaces.

To this end, each Forum 2021 session began with the Code of Conduct (https://www.diglib.org/about/code-of-conduct/), followed by Indigenous land and ancestral acknowledgements that were locally-specific, thoroughly researched and made contextually relevant to each person and project. Inviting all participants to take responsibility for ourselves, each other, our differences and our collective colonial / colonized patrimonies can be sobering if you let it, and with them DLF has been effectively building info-culture and workplace cultural change into its practices, modeling principles, tools and methods of engagement that balance professional rigor with humanizing care and the discipline of sustained structures.

Although this anti-oppression and inclusive culture may have seemed second nature to younger Forum attendees, there is a depth of intentionality and emotional labour that made it happen. This is where DLF Forum 2021 can claim crucial success: In its processes of bold, persistent, meaningful collective change through open and principled access to the working groups, the collaborative relationships, the documentation, and the enlivening of care from beginning to the end, where Nisha Mody artfully inspired participants how and why we must carry the care work forward.

* For this article I use librarians as a stand in for librarians, archivists, curators and data specialists.