Carissa Pfeiffer (@carissapffffft) is a graduate student at Pratt Institute and NYARC Web Archiving Fellow at the Frick Collection who attended MCN’s annual meeting as a Kress+DLF Cross-Pollinator Fellow.

I had the opportunity recently to attend and participate in MCN 2017, thanks to a fellowship from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the Digital Library Federation. The Kress+DLF GLAM Cross-Pollinator Fellowship was created to cultivate connections between those who work across cultural heritage fields, and my takeaways from the conference were informed by my interest in digital preservation and my experience with web archiving at the New York Art Resources Consortium.

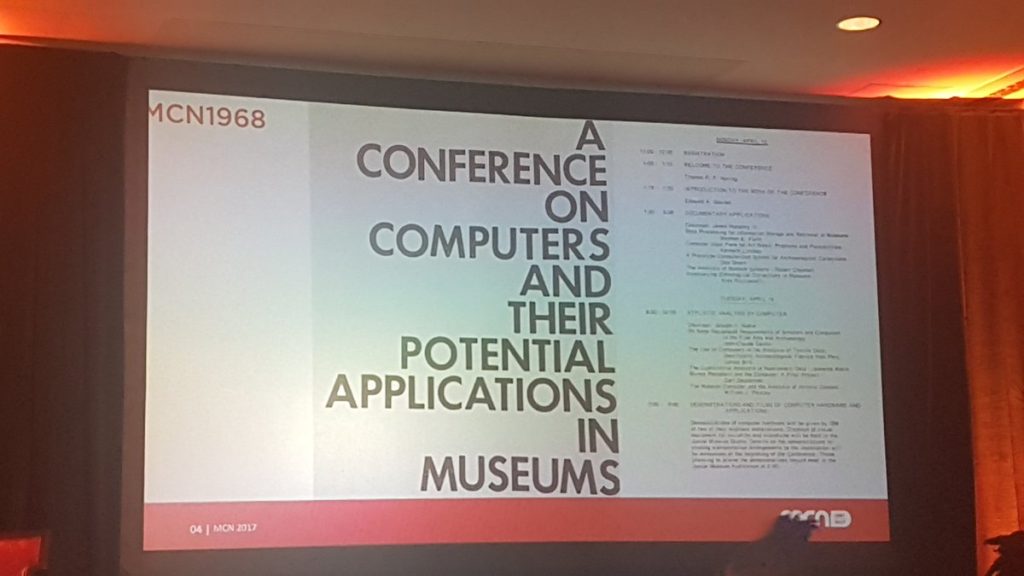

As a current student just beginning to enter the museum world by way of libraries and archives, I especially loved the serendipity of getting to be here for the 50th year of MCN (Museum Computer Network). I benefited from not only the perspectives of many others currently working in all sectors of the museum world, but also the context of the previous fifty years. I’m so glad I got to join in the celebration!

Birthdays mark the passage of time, but they’re also temporal thresholds, limina of the past and future. Museums are like this, too: helping audiences see where our world came from and imagine where it might be going. It’s only fitting that the 50th birthday of a conference on museums and technology would turn this perspective on itself. This year’s theme, “Looking Back, Thinking Forward, Taking Action,” was only fitting.

Looking Back

The team that led the session Mining 50 Years of #Musetech discussed their project analyzing technology in museum job descriptions and titles over the years, found the first mention of computer technology in a job posting in an ad from January 4, 1970. (The Met needed a financial analyst; the ad read “awareness of computer application helpful.”)

Over the years, “awareness of computer application” has pervaded every department within a museum, and production of digital content has exploded. Social media, databases, APIs, apps, interactives, 3D models, augmented and virtual realities… The variety of formats and file and the need to maintain the hardware and software that can read them alone make digital preservation a daunting task.

But it becomes a little less daunting if you’re not alone. The people and presentations of MCN made it clear to me just how deeply collaborative digital production and maintenance are. Or can be. Or strive to be. And should be! The MCN job history project mentioned above traced trends in technology-related job titles, and discovered that in the past twenty years, technology-specific roles started becoming part of museum leadership.

Maybe this only goes to show that twenty years ago, digital departments became large enough silos within institutions that they needed their own leaders. But maybe it means there’s increasing opportunity for top-down support that will help departments across an institution engage in shared sustainable practices in creating digital resources, deciding what’s important, and ensuring that they continue to be used and reused.

Thinking Forward

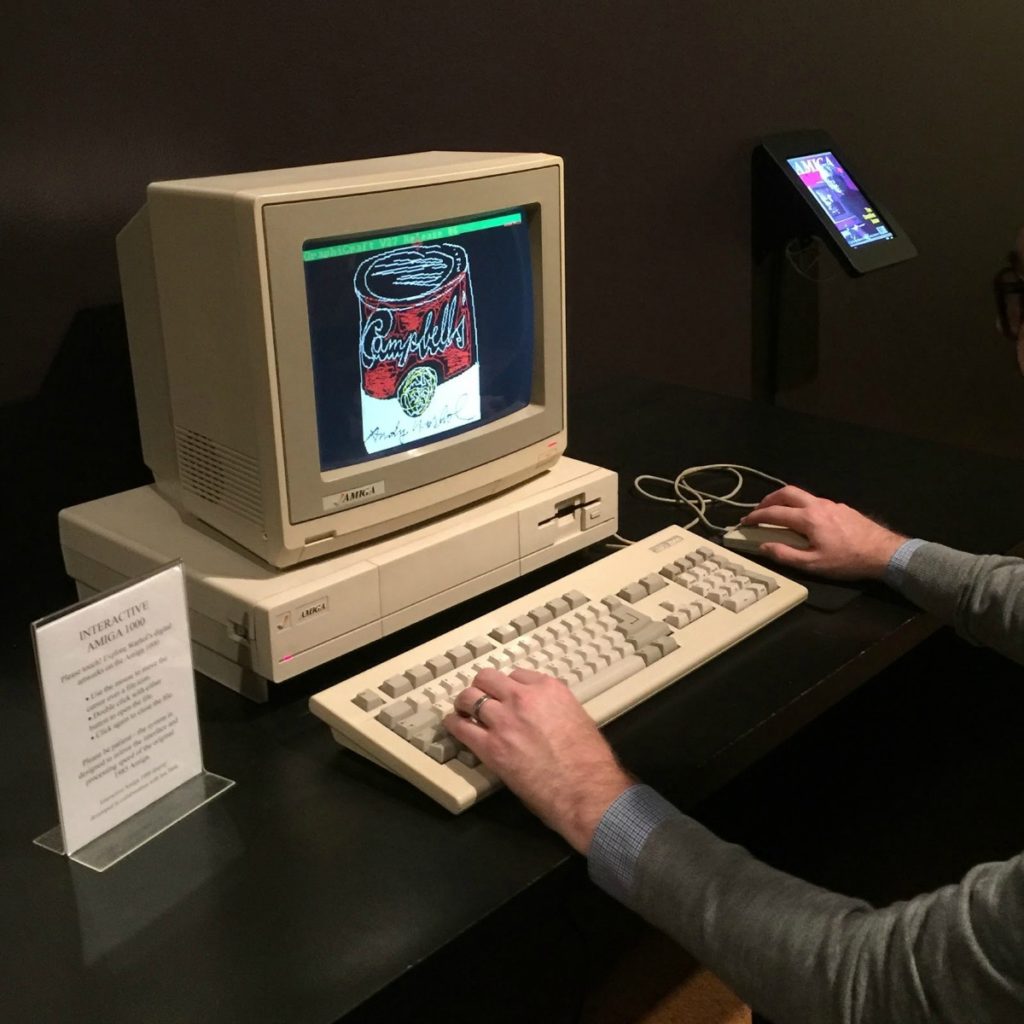

MCN’s 50th anniversary party was held at the Andy Warhol Museum, where you can see Warhol’s digital artworks interact with Amiga 1000 as he would have done in 1985. Extracting the content from floppy disks and reverse engineering the software to make the obsolete .pic files readable was a major effort, described in more detail in the Studio for Creative Inquiry’s report.

MCN’s 50th anniversary party was held at the Andy Warhol Museum, where you can see Warhol’s digital artworks interact with Amiga 1000 as he would have done in 1985. Extracting the content from floppy disks and reverse engineering the software to make the obsolete .pic files readable was a major effort, described in more detail in the Studio for Creative Inquiry’s report.

In the session Digital Preservation for All: Networking Communities to Save Our Digital Heritage, I learned how NDSR Art residents are working together to develop standards solving specific digital preservation needs at distributed host institutions, but that’s not all. The wider digital preservation conversation can’t be limited to digital preservationists, and I was pleased to discover at MCN that issues related to developing sustainable practices and lasting digital products from were at the forefront of the top minds working in the museum field.

Actively promoting use and engagement is key to ensuring that digital resources and projects don’t lose the support they require for their maintenance and preservation, too. In the very first session I attended, Money, Data and Power: A Review of Museum Use Cases with Big Data Analytics, Angie Judge emphasized that professionals analyzing data to track their museum’s visitor traffic, merchandise patterns, digital experience engagement, and more can’t treat data-driven culture as an “if you build it they will come” scenario. Having the data doesn’t mean the initiative will gain traction, if you can’t prove its usefulness.

The same is true for digitized collections and digital tools that museums make available. In #OpenAccess, Now What?, panelists discussed the production and promotion of digital scholarship, now that an increasing number of museums are making their collection’s images, datasets, and APIs available online.

Jeff Steward explained how projects like Nomisma, which made use of Harvard Art Museums’ open data about the coinage in their collections, adds value to the data and encourages further use. In the same presentation, Elena Villaespesa described the success the Metropolitan Museum of Art has had with leveraging platforms like Wikipedia, ARTstor, Pinterest, and DPLA to increase awareness of their digital collections.

Taking advantage of intermediaries was a strategy echoed in another presentation, Becoming Discoverable: Experiments in Marketing Online Publications, in which Lauren Makholm described the challenges of measuring engagement and reaching the right audiences for The Art Institute of Chicago’s digital catalogues as they continue down the path laid by the Getty Foundation’s Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative (OSCI).

On the technical side of things, many presenters spoke to the need for ensuring that digital tools and processes are simple, standardized, accessible, and interoperable for all the users involved, from internal employees to visitors. The fewer intermediaries there are between users and the information that you hope to pass on to them, the easier this information is to reuse and extend for new purposes–and the easier to ensure its preservation, too!

In Open Source Reality Check, Ruben Niculcea and Aron Ambrosiani explained that like digital publications, open source tools also have a marketing issue: people have to know that they will work for them. The success of a partnership in the development of an open source audio guide to serve the unique needs of both the Warhol Museum and Nordiska Museet relied in part on beginning the development process anticipating what needs new users might have–for instance, separating the user interface so that the app can be easily re-skinned to match the branding of another museum.

Software development practices can be applied to more traditional output, too, to optimize control and accessibility. In Data-driven Approaches to Publishing, Eric Gardner described how thinking of text as data and using plain text files rather than WYSIWYG interfaces for museum publications offers enhanced version control, accessibility, and the freedom to choose formats and presentation methods that work best for several purposes.

Finally, the panel Guerrilla Glue: Making Collaborative Digital Innovation Projects Stick expanded into the human relationship component of digital initiatives. Although the session was rooted in technology (“operationalize your Linked Open Data!” might be among the jargon-iest notes I took) a number of speakers made specific recommendations for creating sustainable projects centered on building solid partnerships.

Human relationships and organizational culture, this final panel made clear, are the most foundational resources to develop. If everyone involved has a sense of their role and importance in a project, it generates commitment to developing and maintaining long-term, interoperable standards–a critical component of any project or resource that is supposed to have far-reaching impact. Collaboration can also be a sustainability measure: shared knowledge can survive turnover and organizational change.

Taking Action

Keynote speakers Adrianne Russell, Aleia Brown, and Jamil Smith in conversation about integrating missions beyond the museum walls with institutional goals, decentering dominant narratives, and “understanding who has done the work and when.”

(Photo taken by @Jennifer_Foley)

There’s lots of work to be done, of course. Matthew Lincoln’s thoughts on this conference with regard to museums’ apparent inability to build and implement community standards that carry across institutions tempered some of the starry-eyed optimism I left MCN with, and his points are legitimate. The sense of anxiety and disillusionment described by Rachel Ropeik in another blog post is real, too: self-care talk was pervasive.

I think these issues are interrelated. There are problems with organizing an institution around principles of grit and resiliency rather than stability and standards. I know a number of sessions that I wasn’t able to attend addressed these points, so I look forward to listening to the conference session recordings.

But it still seems significant to note that the projects described in the sessions above encompass all organizational levels and all types of roles, from curators to archivists, tech developers to educators,and the wider community outside of the museum. And there was one more theme that came up again and again in different (not always technology-specific) contexts throughout the conference, from the keynote to the very last presentation I attended: acknowledging and making deep use of the work that has already been done.

This is where I see the greatest potential for people from different professional backgrounds to come together and see what issues other disciplines are working through. If professionalism is largely knowing the right vocabulary for your field, as one of the speakers on the Guerrilla Glue panel noted, then digital projects require more professionals who can communicate across those language barriers and expand our common language. It’s important to learn respect for how other people and professions operate, as well as to trust and draw on their expertise to solve the problems we all share.

So I’ll close out with another reminder of the magic of liminal spaces. Distinctions between professional roles aren’t so much boundaries as they are borderlands, and fertile ones at that. I’m immensely grateful that Kress and DLF are generously enabling this through Cross-Pollinator Awards like the one I received, and I hope we see more people willing to traverse these borders. I hope we all keep listening and learning from each other.

And hey, MCN? I also hope I get to join you for your 51st birthday in Denver–a year older and a year wiser!

Carissa Pfeiffer

NYARC Web Archiving Fellow, Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection

MSLIS Candidate at Pratt Institute School of Information