This post was written by Lisa Covington (@prof_cov), who was selected to be one of this year’s virtual DLF Forum Community Journalists.

This post was written by Lisa Covington (@prof_cov), who was selected to be one of this year’s virtual DLF Forum Community Journalists.

Lisa Covington, MA is a PhD Candidate at The University of Iowa studying Sociology of Education, Digital Humanities and African American Studies. Her dissertation work is “Mediating Black Girlhood: A Multi-level Comparative Analysis of Narrative Feature Films.” This research identifies mechanisms in which media operates as an institution, (mis)informing individual and social ontological knowledge.

In 2020, Lisa received the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Award from the Iowa Department of Human Rights. She is the Director of the Ethnic Studies Leadership Academy in Iowa City, an educational leadership program for Black youth, in middle school and high school, to learn African American advocacy through incorporating digital humanities and social sciences.

Lisa received her MA from San Diego State University in Women & Gender Studies. As a youth development professional, Lisa develops curriculum for weekly programming with girls of color, trains teachers on best practices for working with underrepresented youth, and directs programs in preschool through college settings in California, Pennsylvania, Iowa, New Jersey, New York and Washington, D.C.

What is DLF? Where does equity fit into conversations? Is this a space where my scholarship is valued? These are the questions I asked myself as I planned to attend my first DLF conference. I was uncertain about the DLF community and what would be considered worthy of discussion in this space.

These were the thoughts I had as I prepared for the opening plenary of the 2020 DLF conference. Honestly, I was hopeful when I saw Stacey Patton was speaking. I am familiar with her work as a historian, professor, journalist and as an advocate on behalf of Black children. Hopeful, I listened and learned. One thing that Patton said that remained with me throughout the conference:

“Galleries, Libraries, Archives & Museums (GLAMs) reflect the ways in which white people colonize information but also serve as gatekeepers of information related to themselves. When archives were originally set up, Black names weren’t important unless they were attached to the names of an important white person who owned slaves or was some kind of white savior to Black people.”

As I understood Dr. Patton’s statement during the DLF Opening Plenary, I was glad to hear those words for two reasons. It was refreshing to have a conference begin on the note of connecting modern-day oppressions to the profession and, secondly, the serious impact it has on Black and Brown people and the archives that reflect our identities.

The uprisings and protests taking place in 2020 demanding the end of police brutality while asserting Black Lives Matter across professions, walks of life and locale. The marches, the rallies and public outcry demand the end of police brutality while declaring Black humanity is worthy of existence: a sign of the times. Today, as we prepare to enter 2021, we can no longer point to the 1960s as winning the fight for civil rights. Will the history books say that we were on the side of justice or oppression?

We collectively bear witness to social unrest stemming from state sanctioned violence against Black men, women and children in the United States. What followed was mass deployment of solidarity statements across universities, businesses and organizations. Also, during this time, people across careers trajectories and higher education fields often went to Twitter to talk about how their employer needs their opinion, the lack of inclusive curriculum or their department asks them to be on the diversity committee of one. It was the first time I had ever witnessed a collision between social injustice, academia and organizations. So why now? Why was Patton daring us to challenge oppression when it appears that releasing statements is enough?

But then I thought about moving across country for graduate school. No university official checked on my well-being even though it was months after Sandra Bland was murdered in Texas. When Alfred Olongo was murdered in California, no teacher or administrator at any school I ever attended asked how this impacted me as a student. But now: an abundance of statements addressing equity?

Our work with archives is no different. We can make inclusive claims or create just practices.

During the DLF opening plenary Patton’s acknowledgement to us of the daily violence—physically and disciplinarily—allowed us to honestly consider the necessary but difficult work of implementing just practices. She asked for and demanded accountability for the historical neglect of Black archives across GLAMs.

Patton further asked, “…is there a version of this kind of erasure happening in the galleries, libraries, archives, museums where there’s still baked-in inequality from a century ago?” The answer to this is clear in what is preserved with intention and what is ignored. Whose history is preserved? What history is deserted? As curators, stewards and preservationists, it is our duty to develop intentional, concrete practices to ensure oppression does not continue in GLAMs. The possibility of this rests in our daily and hourly commitment, or negligence, to just practices.

It was hopeful to see several BIPOC folks and allies model commitment to justice and equity throughout the digital humanities.

In honoring an elder and first archivist at Allen University—Ms. Wilhelmina Broughton—Carol Bowers, Courtney Rounds & Sloane Clark shared the curation of the archive. Ms. Broughton contributed much to South Carolina communities during her 30 years of teaching in public schools (1964-1995) and work as the first archivist at Allen University for 20 years (1999-Present). As with many of our institutions, when one person leaves their knowledge leaves with them, but we see other possibilities through what Allen University created: honoring a living legend and incorporating Ms. Broughton’s institutional knowledge, with PastPerfect software, to create the archive.

Another session brought a thoughtful approach to Black people who were victims of state sanctioned violence. In her presentation on systems honoring these victims, Gina Nortonsmith of the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project thoughtfully included trigger warnings. I have rarely heard it used in relation to the state sanctioned murders of Black people. Prior to describing the mind mapping process and data dictionary creation for the Burnham Nobles Digital Archive, the audience was informed to turn the volume down due to the violence that would be described and given a visual cue signaling to turn the volume up again. When I thanked her for this gesture she explained: The stories are important to center, but I try to do that in ways that honors victims and the audience.

This simple gesture is recognition that Black people— specifically descendants of enslaved Africans in the Americas—may be harmed due to the seemingly normative, repetitive occurrence of witnessing state sanctioned violence such as the murder of Aiyanna Jones. Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project are documenting the historical crimes against victims of racial violence.

My entire educational career has encouraged me to be comfortable with cruelty and maltreatment of people who look like me, especially during the enslavement of Africans, Jim Crow Era, Civil Rights Era and within the Obama years and after. But Nortonsmith’s comment and incorporation of trigger warnings illustrates that it only takes moments to demonstrate thoughtfulness to respect the lives of those within the archives as well as those may be significantly impacted.

I recognized the significance of trigger warnings when I had to stop watching a different session focused on Minnesota’s summer uprisings as a result of George Floyd’s murder. There was limited context and no trigger warning of the anti-Black violence that would be discussed. I don’t know if I will ever watch that presentation. But I do know, several other sessions and resources continued to challenge the ways in which archives can perpetuate oppression.

- The Center for Black Digital Research #DigBlk and the Colored Conventions Project, a foundational model in centering marginalized people in the archives.

- The United States Latino Digital Humanities Scholars, founded at the University of Houston explain the archive as a space to create culturally responsive curation protocols developed with scholars, community members, cultural practitioners and students.

- The rejection of normative white cishet language in constructing metadata.

- Creation of a digital humanities course that began the work of analyzing independent newspaper, El Diario de la Gente, by Chicanx students at the University of Colorado-Boulder between 1972-1983.

- Digital Black History, a searchable resource for online projects furthering Black history

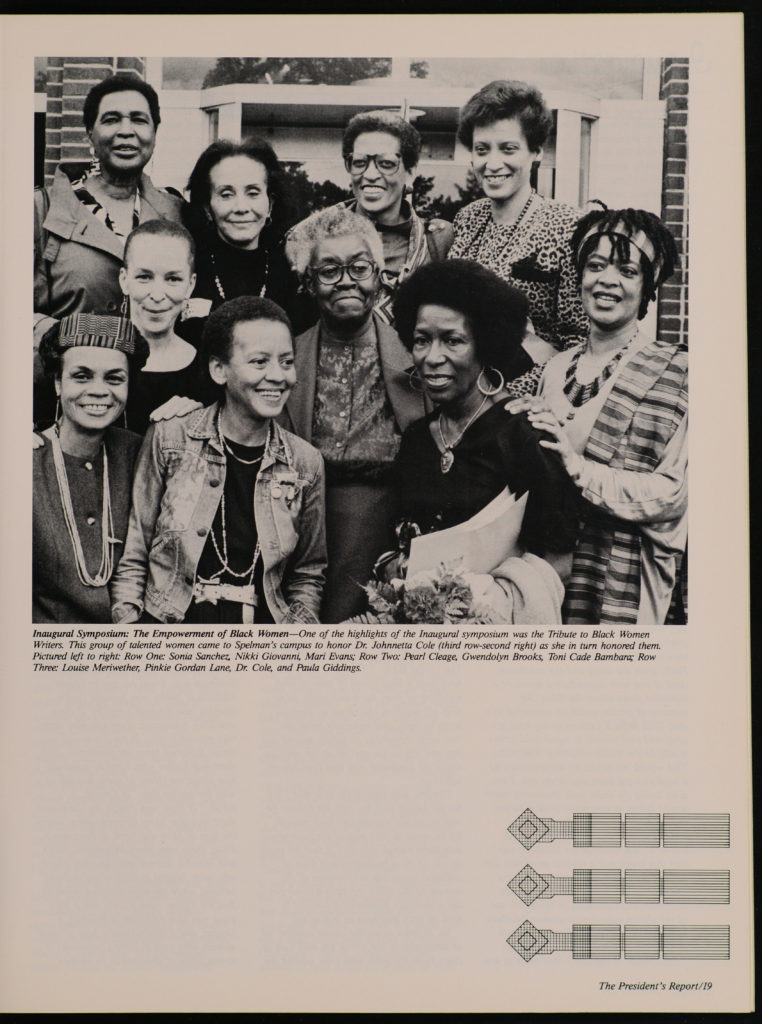

- Atlanta University Center’s collaborative between Spelman College, Morehouse College and the Digital Library of Georgia including Black Women’s Suffrage Digital Collection and an archive of the campus newspaper, Spelman Messenger since its inception in 1885

With all of these examples as models we know that Black and Brown humanity can be prioritized over the white colonization of archives Patton described. Black and Brown lives—and deaths— can be sovereign in the archives. It is up to our intentional actions on behalf of justice or oppression. Which actions will you take?