This post was written by Amanda Guzman, who was selected to be one of this year’s virtual DLF Forum Community Journalists.

This post was written by Amanda Guzman, who was selected to be one of this year’s virtual DLF Forum Community Journalists.

Amanda Guzman is an anthropological archaeologist with a PhD in Anthropology (Archaeology) from the University of California, Berkeley. She specializes in the field of museum anthropology with a research focus on the history of collecting and exhibiting Puerto Rico at the intersection of issues of intercultural representation and national identity formation. She applies her collections experience as well as her commitment to working with and for multiple publics to her object-based inquiry teaching practice that privileges a more equitable, co-production of knowledge in the classroom through accessible engagement in cultural work. Amanda is currently the Ann Plato Post-Doctoral Fellow in Anthropology and American Studies at Trinity College in Hartford, CT.

On Belonging:

There is that decisive moment for me at every academic conference that I’ve ever attended – whether it is one that I frequent regularly (even annually) or one that I’m trying out for the first time like the DLF Forum this year – where I’m sketching out my trajectory of movement and negotiating what my belonging might look like in the space. This moment exists in the scanning of the conference program and translating of different panel abstracts. This moment exists in those standstill seconds in the threshold of a panel room as you decide whether to enter or not, perhaps as you notice a familiar or friendly face.

Our current pandemic moment has transformed how we collectively gather in profound ways and brought into sharp relief the pre-existing structural social inequities of access. And yet, the decisive moment of my new belonging in the space of the DLF Forum was from a distance, and yet was not solitary beginning with a wave of introductions among first-time attendees and offers by long-time Forum-goers of support on Slack and extending to the generosity of time, experience, and transparency offered to me by my DLF mentor, Maggie McCready in our Zoom conversations. The decisive moment ultimately resolved, as I left the metaphorical door threshold to take a seat, during Dr. Stacy Patton’s keynote as she seamlessly moved between commentary on national news, archival text, pedagogical practice and her own powerful personal narrative of coming to belong in spaces not made for her experience and of coming to build new spaces of belonging.

Activating the Archive by Reframing History as Practice:

One of the most compelling interventions that Dr. Patton articulated in her keynote speech was a call for the DLF community to reframe their implicit understanding of history not only as a physical archive of a material past but also as an active departure point for our contemporary reorientation and empowerment. Interweaving meaning and purpose across institutional case-studies, she referred to the concept of “historical touchstones” that present us with “context, guidance, and perspective” that have the analytical potential to ground our experience in the positionalities as a “keeper of knowledge” with a “traditional role of being…guide” to students.

Keepers of Knowledge:

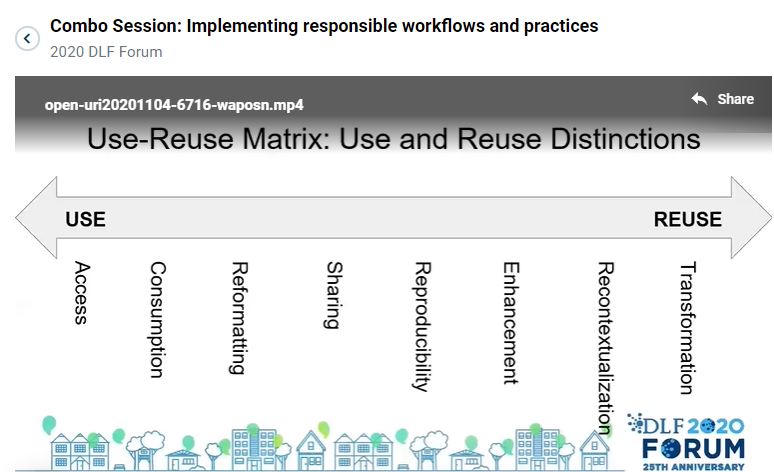

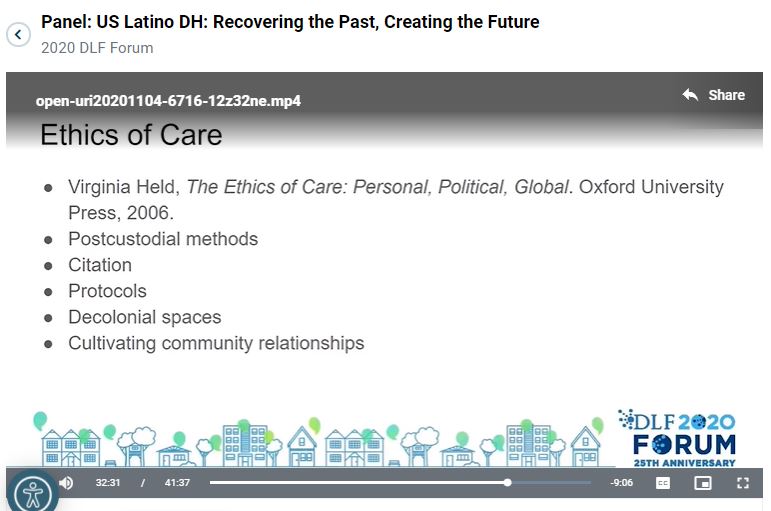

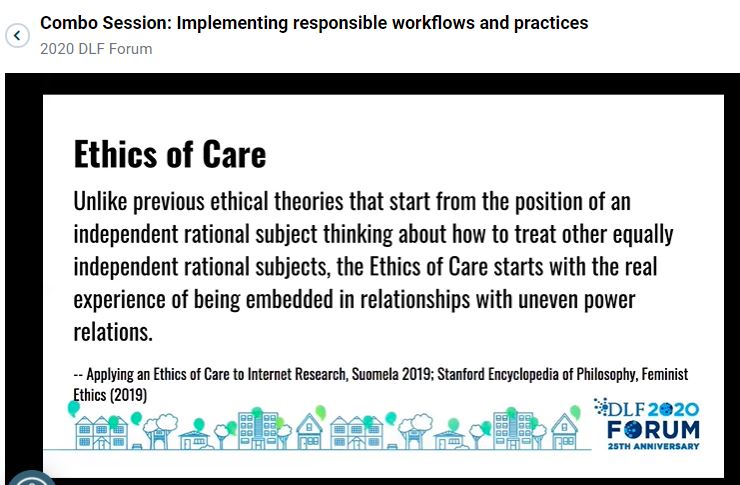

This proposal of mobilizing history towards how we critically approach our present-day practice in the field echoed throughout the subsequent forum presentations and was especially materialized for me in the citational acts of emphasizing a theoretical focus on an ethics of care. In the “Combo Session: Implementing responsible workflows and practices,” ethics of care was centered in an appreciation for “relationships with uneven power relations,” a methodological re-framing of both those actors who study and those communities who are studied as equal “independent rational subjects” and a researcher responsibility to identify the multi-faceted capacity of archival work to inflict harm. This work was discussed, for example, with the case-study of the archival process at the University of California, Berkeley for selecting indigenous cultural material for digitization and if to be digitized, under what terms of public access. In other words, professional ways of working were recast beyond the technicalities of how archival material may be best processed and digitally preserved to include and more importantly, to privilege a recognition of academic histories of community extraction and an opportunity for academic futures of more collaborative, equitable workflows.

Student Guides:

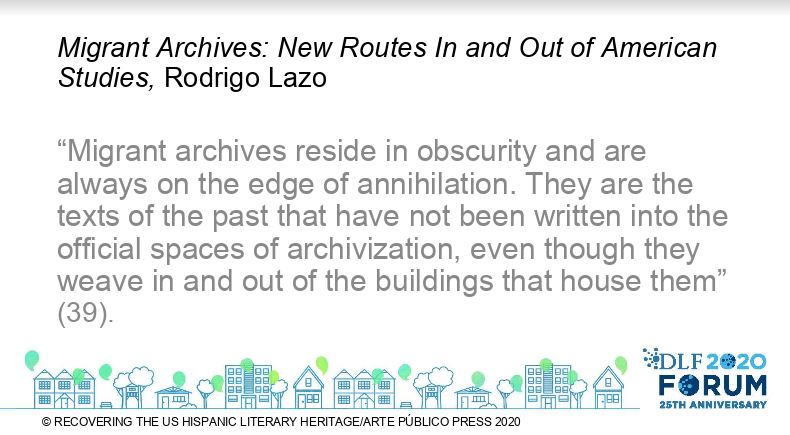

Building on this important reflection on institutional practices, the US Latino DH panel entitled, “Recovering the Past, Creating the Future” brought the historically based practice conversation into the context of the undergraduate classroom. During their presentation, I was reminded of Dr. Patton’s earlier caution that digital work could not be the “end all be all” (even among undergraduates who are often thought to be “digital natives”) given how it is “alien to flow of time…nuances” and “abbreviates how we understand things”. Presenters Carolina Villarroel, Gabriela Baeza Ventura, Lorena Gauthereau and Linda Garcia Merchant accepted the challenge and outlined a pedagogical design that built a student theoretical consciousness of the silences inherent in archival representations of the human experience and equipped students methodologically through programs like Omeka to emerge as digital storytellers of new stories. Moreover, the presenters destabilized the curatorial authority of collection-holding institutions by decolonizing where and how we locate archives with models such as post-custodial archives (describing archival management in which the community maintains physical custody of material records) and migrant archives. Both panels therefore expanded the boundaries of what constitutes archival practice – in terms of how we keep existing knowledge and how we teach knowledge production – by expanding what we care for to who we care with.

At the Close:

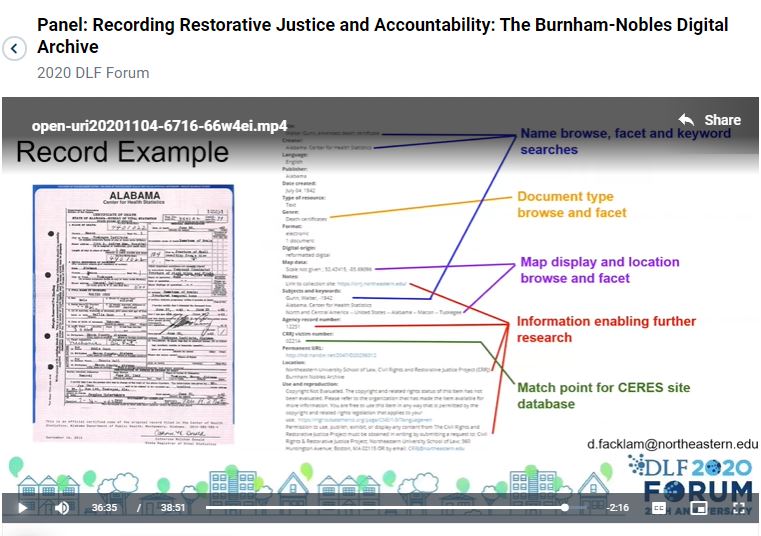

Aliya Reich, Program Manager for Conferences and Events at the Digital Library Federation, remarked at the start of the forum that the goal of our gathering was “building community while apart”. Joy Banks, Program Officer at the Council on Library and Information Resources, responded on Slack to a participant struggling with the digital conference platform that “there is no behind this year”. Together, their words bring me – in concert with Dr. Patton’s keynote assertion of our roles as “guardians of the past and present” and “architects of the future” – that we the practitioners – our bodies, communities, experiences, professional practices and all – are directly implicated in the work that we do every day to record and to preserve. That work does not and cannot exist in isolation from the privilege and marginalization of our lived realities whether in terms of arts funding austerity to ongoing national social justice movements.

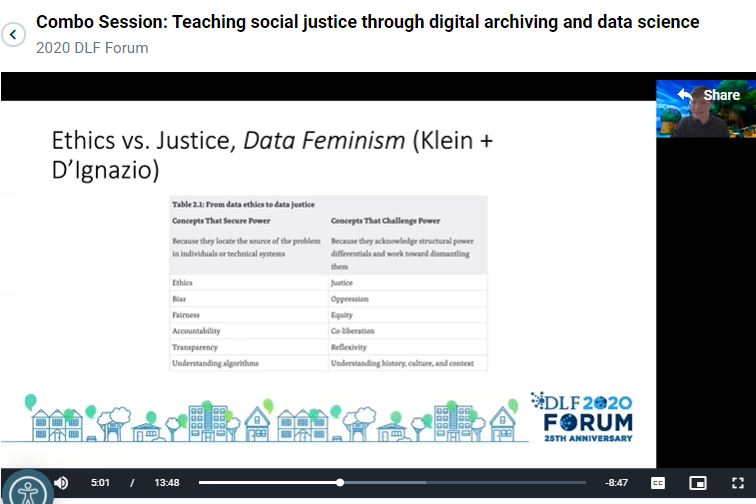

The archive is a product in large part of human decision-making. We as a community can be reflective in practice with data justice over data ethics models that recognize the source of power and aim to dismantle structural power differentials. We as a community can choose to accept complexity of human behavior and spectrum thinking over binary dichotomies. We as a community can participate in mission-driven archiving in the present that supports restorative justice of the past – by upholding archival protocols that prioritize dignity and respect towards underrepresented, vulnerable communities who have and continue to endure systematic trauma. In building a community while apart we can ask who is and where is the community; the answer is in but also and perhaps in some cases more importantly, beyond our conference panel rooms.